First the entire village is shooed indoors, its power supply is cut, and finally bananas and other elephant treats are dumped on the opposite side of town to coax the uninvited guests to pass through.

So goes the routine welcome ceremony for China’s wayward herd of 14 wild elephants, whose wandering ways have sparked an unusual operation aimed at steering them home across steep, winding, and often populated terrain.

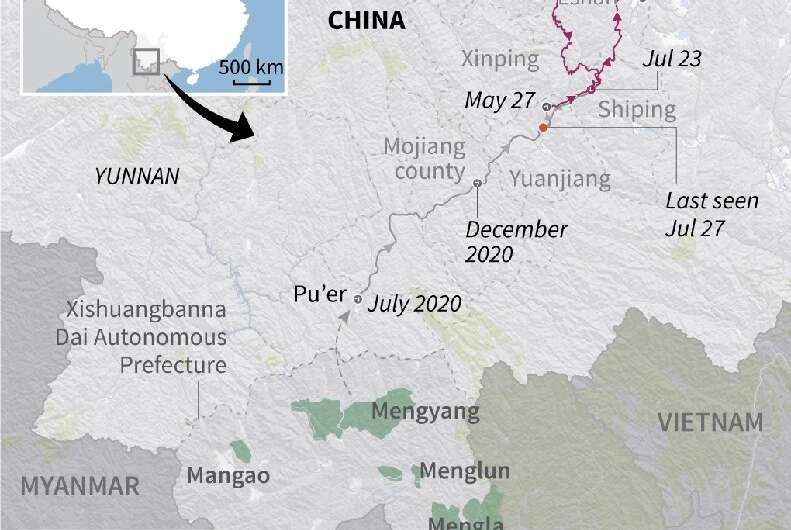

The group left its home range far south near the Laos border 16 months ago for a grand food tour across rich farmland bursting with corn, sugarcane, bananas and dragon-fruit in southeastern Yunnan province.

The Chinese public has delighted in the elephants’ antics, including parading down city streets, guzzling grain alcohol and dozing en masse in a field.

Jumbo task

But it’s a jumbo task for the three dozen Yunnan forestry firefighters charged with shepherding the elephants safely home—tracking night-moving animals that can disappear into thick forest and trek up to 30 kilometres (18 miles) a day.

It’s the furthest north that China’s wild Asian elephants have travelled in recorded times, said Yang Xiangyu, a task force leader.

“Before this, we only saw elephants in the zoo or on television,” he said.

Alarmed officials formed the task force in May, as the elephants neared Kunming, the regional capital.

Using drones to keep tabs on the animals, they sleep out in the subtropical air or in their vehicles.

On a recent morning team members stood before a large-screen TV in a temporary village headquarters as front-line colleagues beamed back the day’s first images.

As white clouds parted, unmistakably elephantine gray-brown outlines appeared down in a forest clearing near a village, their trunks probing around for a final snack before bedding down during the daytime heat.

They stir again around dusk, and their trackers move with them.

When they approach a village, loudspeakers and door-to-door checks urge locals to shut themselves in, preferably upstairs, out of reach of the hungry visitors.

Power supplies are cut to prevent the elephants from electrocuting themselves or sparking fires, and vehicles are parked across roads behind the herd or on side routes to keep them moving forward, preferably south.

Once through, their new location is plotted, the weary task force redeploys and the circus resumes the following dusk.

Smart and deadly

The elephants have dazzled their chaperones with their intelligence.

A mature female leads, always finding the best path toward food and water or the safest point across a stream, Yang said.

They use tree branches gripped in their trunks to help comrades scratch a hard-to-reach itch, swat bugs, or seemingly draw designs on the ground.

Mud is employed as sunscreen, they may fashion a crude “sunhat” out of vegetation, and their dexterous trunks can turn on a faucet, open a door, or lift covers off water wells for a drink, Yang said.

There are three juveniles, two born during the odyssey, officials said. Adult elephants have been seen using their huge bulk to crush down traffic guardrails so the youngsters can clamber over them.

China’s state-controlled media has cast them as the lovable protagonists in a national lesson on conservation.

But the elephants, which can weigh up to four tons and sprint as fast as Usain Bolt, are also extremely dangerous, particularly if they sense a threat to their young.

Two of them who earlier broke for home trampled a villager to death in March, said Chen Mingyong, a Yunnan University elephant-behaviour expert attached to the task force. The fatality appears not to have been reported.

“This needs to be faced squarely. The Asian elephant is a wild beast and we have to keep a safe distance,” Chen said.

Media are kept away from the animals on safety grounds.

Mystery migration

Why the elephants began their trek remains a puzzle.

Possible explanations include tighter competition for resources due to an increase in wild elephants in their home range.

Climate change may also be subtly affecting their habitat, Chen said, or fluctuations in the earth’s electromagnetic field could have thrown off their finely-tuned navigational sense, or they may have simply taken a wrong turn.

Researchers are particularly stumped over why the skilled navigators made a nearly straight beeline for Kunming before angling back south a couple months ago.

Elephants typically circle around in their hunt for food, Chen said.

“There have been many behaviours for which we previously have not had sufficient data.”

They’ve travelled more than 700 kilometres, Yang said, and though now pointed homeward, still have several hundred more to go.

And the smart foodies appear to be slowing, unwilling to rush through the cornucopia ripening around them in the summer sun, Chen said.

But cool autumn weather is expected to eventually hasten them home, a bittersweet prospect for Yang and his team, who have become attached to the gate-crashers.

“As soon as (trackers) see the elephants on our monitors, they feel very happy despite the hard work and toil,” he said.